Readiness, Resilience, and Respect

Why Foundational PYD Research is More Important than Ever.

It’s an honor to have the opportunity to talk with you today. I’ve had the pleasure of not only working with 4-H leadership but presenting at 4-H conferences several times over the past three decades, working with Don Floyd, Jennifer Sirangelo, and now Jill Bramble whom I just met last night for dinner.

It’s a treat to have an opportunity to return a favor to Mary Arnold who has never said no to a request to contribute to our efforts to stand up the Positive Youth Development (PYD) approach to youth development …

And it is exciting to have an opportunity to share a bit of the rich PYD history with you on PYD Spotlight Day. When I think about what distinguishes PYD theory and the PYD approach from others, it is the intertwining of three concepts: Readiness, Resilience, and Respect. We don’t always use those terms but, they shine through when we are doing our best work with young people, in particular with teens

Those of you who know me, know that I coined the phrase “Problem-free isn’t fully prepared.”

The slogan is a reminder that our purpose for interacting with young people – even young people in the midst of crises – must be more than ensuring that they are not on drugs, not getting pregnant, not dropping out, not committing crimes – even when thinking that young people need to be fixed before any efforts to develop them will stick is counter to the science).

I used to emphasize this point by asking conference participants, after describing Juan, a hypothetical 18-year-old job candidate with a series of not statements (he is not a drop out…) if they would hire him. A few would say yes. But I could always count on someone in the audience to call out “What can he do?”

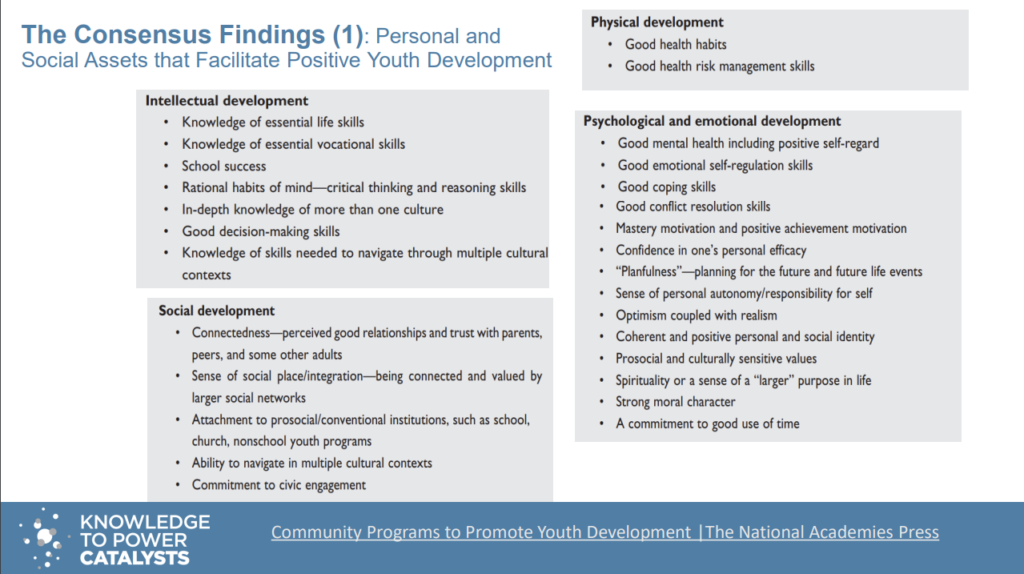

That mantra struck a chord with researchers and practitioners who were seeing the advantages of taking an asset-based approach to the prevention and remediation of youth problems. We hit pay dirt when the National Research Council decided that there was sufficient evidence to stand up a study commission. Their 2002 report, Community Programs that Promote Youth Development, galvanized the field. Their summary findings about the domains of assets that support youth development and the characteristics of settings that support it are still used as touchstones by researchers.

The mantra (which someone had made into a wall clock for me as a speaker’s gift) was only the first line of a longer set of declarative statements. Problem-free isn’t fully prepared. Academic competence isn’t enough. Competence in and of itself isn’t enough. Later, once we were convinced people understood what we meant by fully prepared, we added a second slogan. Problem-free isn’t fully prepared. Fully prepared isn’t fully engaged (to emphasize the importance of agency, identity, and meaningful contribution..

Last year (November ‘22), I got a call from a reporter, wanting to be referred to programs that address the youth mental health crisis. When I began talking to him about broader solutions (even MTSS), I could sense his frustration. He told me he was asked to write about mental heath services but people kept referring him to more general solutions. I explained the logic behind asset-based approaches to supporting young people that don’t ignore or give short shrift to their problems, but also don’t focus on them with such singularity that young people feel stigmatized. I mentioned the NRC report. That helped, but only a bit.

He asked me, somewhat deflated, if I had suggestions for a question to ask the Surgeon General when he interviewed him the next day. I promised I would reread Murthy’s Protecting Youth Mental Health Advisory and get back to him before the end of the day. The Advisory was pitch perfect. I sent him a question.

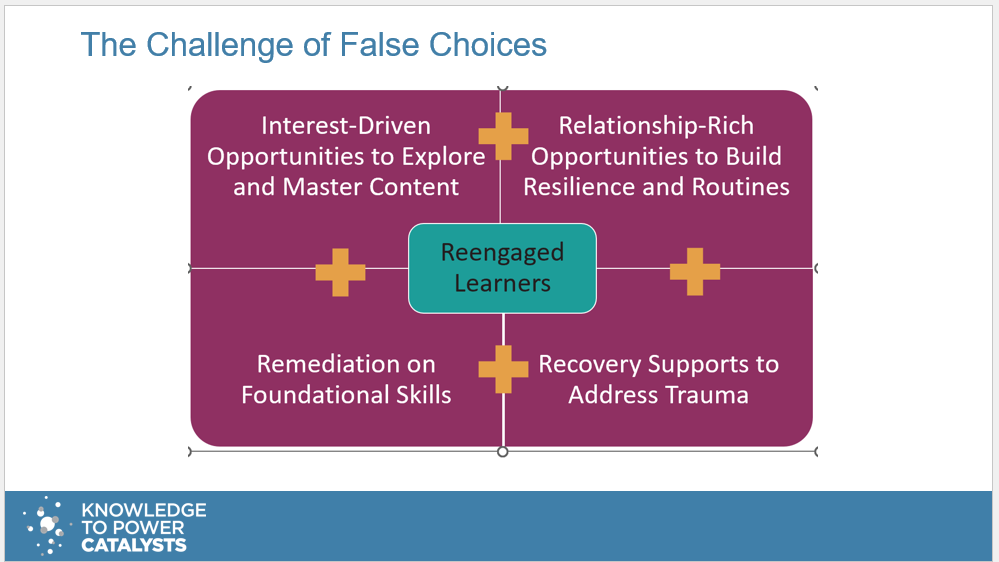

As the interview with the reporter demonstrated, the media often reinforced the perception that we must make all or nothing choices. Which pressing problem to address? (learning loss or youth mental health). Which things to let go of until the problems subside (e.g., relationship-rich, interest driven activities). The question is one of balance – but for individual children and teens, not for the system.

The interview prompted me to make this “either-or” thinking the focus of my next Youth Today column. I amended the slogan in the title: Fully prepared doesn’t require being problem-free, just resilient. I walked through the story I just told you and ended with these recommendations.

To support young people’s mental health, we need:

- adequate professional treatment and family supportsfor young people with diagnosable mental illness problems.

- non-stigmatizing screening and assessment services available in multiple placeswhere youth and families have connections.

- a steady, generous supply of relationship-rich environmentsthat encourage self-understanding, identity development, and social and emotional skill-building.

And everything we know about adolescence tells us that because adolescents are both hyper-curious and hyper-sensitive, these three distinct types of interventions have to be available for all adolescents all of the time for any to really work.

The same continua of services, supports and opportunities are needed to support learning and development in other life domain cognitive, physical, civic, social.

The same continua of services, supports and opportunities are needed to support learning and development in other life domain cognitive, physical, civic, social.

30 years ago, PYD was introduced to convince policy makers and practitioners focused on preventing or reducing youth problems to raise their sights.

Today, as the country scrutinizes our public education system, PYD may be the best way to convince educators that they can broaden their sights without sacrificing academic instruction and, equally important, without treading on families’ right to “raise their children as they see fit.”

PYD is about both/and, not either/or. It is about Readiness, Resilience, and Respect. But most importantly, as Michelle Gambone and her colleagues at Youth Development Strategies Inc, argue, it must be linked to short-term and long-term results. And for educators to embrace PYD, it has to be seen as an effective and efficient way to achieve the academic results they are accountable for producing.

I have spent the past 5 years immersing myself in “whole child” education initiatives led by educators. PSELI, Aspen’s SEAD, the SoLD, Education Re, NTC, XQ Institute, moving from speaker, to advisory board member, to consulting advisor, to partner. My initial goal was to look for ways to blur the lines between in school and out-of-school learning. As Mary said, I stepped away from the Forum to do this full time at the end of 2020.

After two years of bringing pieces of PYD into these rooms in pieces, the Knowledge to Power Catalysts partners … decided to invite the education organizations we had relationships with to kick off 2023 by bringing their leadership teams into “Back to the Future” discussions with us in which we took them through a brief history of PYD linking these ideas to current frameworks and research. To date, we’ve offered versions of these presentations to leaders in over 60 education and youth development organizations and networks.

We have different doors into these discussions. Sometimes we start with public opinion surveys. Sometimes with education redesign frameworks. Sometimes with opportunities (like CF+ XQ) commitment to dismantle the Carnegie Unit). Whichever door we come in, we always present what we consider the foundational PYD research studies (e.g., NRC, Gambone). This is the research I want to take you through this morning. It will take about 20 minutes. Then I’ll stop and ask Mary to join me for reflection since this research is beautifully reflected in the 4-H Thriving Youth Framework. And we’ll take questions. But let me pause first to see if Mary has anything to add, or if there are clarifying questions.

The Science of Learning and Development (SoLD) Alliance, a field-building resource hub for researchers, practitioners, and policy makers committed to translating rigorous research on how learning happens for field use, offers this summary of its extensive, multidisciplinary research review:

Every child, no matter their background, has the potential to succeed in school and life. But no two young people learn in precisely the same ways. Cognitive, social, emotional, and physical growth are extremely uneven within and between children. There is no average learner.

Learning is social and emotional. The environments, experiences, and cultures of a young person’s life are more influential than their genes. Children’s ability to learn is strongly intertwined with their social, emotional, cognitive, and physical needs and gifts. Learning in any domain is sacrificed when the whole child is ignored.

Supportive contexts and relationships matter. The human brain is remarkably malleable and can be changed by strong, supportive relationships and the conditions they create. Brain scans show us that learning stops when children don’t feel safe. The amygdala, nested in the temporal lobe, controls the fight or flight function. When this response ratchets up, the capacity to process and remember information shuts down.

The effects of trauma on learners can be reversed. When children experience sustained trauma, the fight or flight switch becomes much more sensitive or just stays on, even in situations adults would assume are safe. But Oxytocin (often called the love hormone) is more powerful Cortisol (the stress hormone). The effects of sustained trauma can be undone in relationship-rich environments.

SoLD Alliance Takeaways. Taking time to build relationships and make sure that learners have a sense of safety and belonging isn’t taking time away from learning. It is laying the foundation for it. The Alliance partners translated their findings on how learning happens into a set of design principles for educators. The five elements in the Blue Wheel are non-negotiables. If any are absent, learning and development and thriving are compromised. But the principles play out differently in different contexts.

Alliance partners created two design principles playbooks – one for teachers, school staff and administrators, one for the staff and directors of community-based organizations and institutions – to emphasize the importance of learners and educators working together to optimize the constraints and opportunities associated with specific settings.

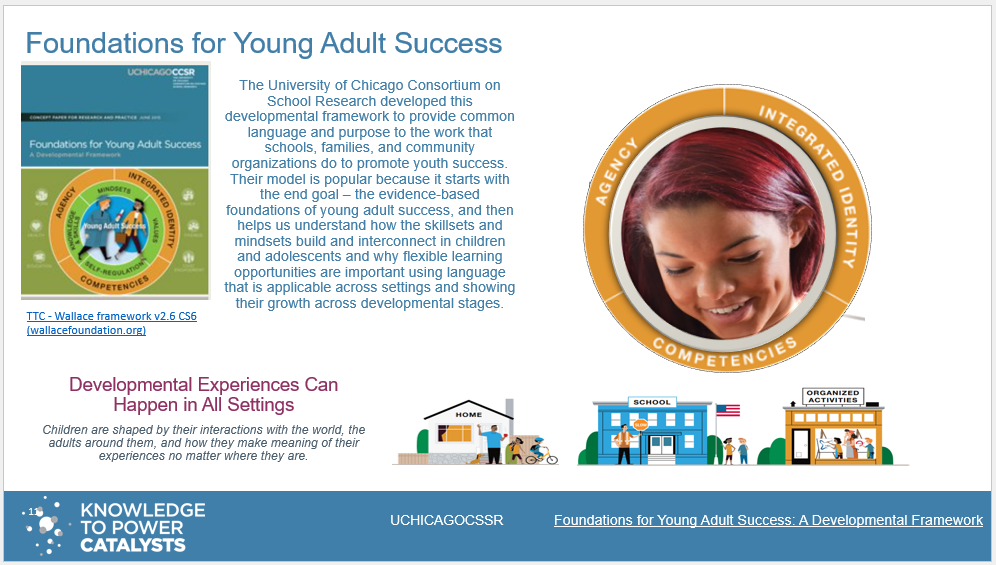

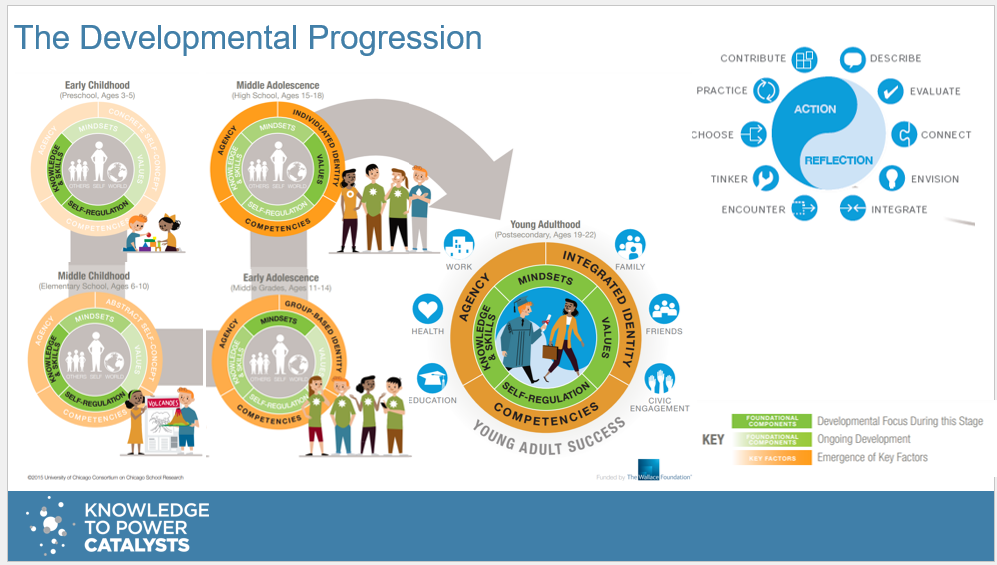

Development of Competencies, Identity, Agency Takes Decades

The University of Chicago Consortium for School Research brings a strong developmental perspective to their work with K-12 schools and community organizations. Given the growing recognition that academic skills alone are not enough for young people to become successful adults, the Consortium did a comprehensive review of evidence both 1) to discern what young people need to develop from preschool to young adulthood to be successful in college, work, and life and 2) to determine the kinds of experiences and relationships that guide the development of these factors in learning experiences in and outside of school. The Foundations for Young Adult Success infographic is visually self-explanatory. A summary of premises and terms includes:

Premise: Children learn through developmental experiences that combine Action and Reflection, ideally within the context of trusting relationships with adults. Over time, through developmental experiences, children build four foundational components that underlie three key factors of young adult success.

Key Factors: Being successful means having the Agency to make active choices about one’s life path, possessing the Competencies to adapt to the demands of different contexts, and incorporating different aspects of oneself into an Integrated Identity

Foundational Components: Self-Regulation includes awareness of oneself and one’s surroundings, and managing one’s attention, emotions, and behaviors in goal-directed ways. Knowledge is sets of facts, information, or understanding about self, others, and the world. Skills are the learned ability to carry out a task with intended results or goals. Mindsets are beliefs and attitudes about oneself and the world, the lenses used to process everyday experience. Values are enduring, often culturally-defined, beliefs about what is good or bad and what is important in life. Values serve as broad guidelines for living and provide an orientation for one’s desired future.

The Consortium’s message: Whether at home or school, in an afterschool program, or out in their community, young people are always developing. Success goes beyond education and employment to include healthy relationships, a meaningful place within a community, and contributing to a larger good.

Broader societal contexts, systems, and institutions shape youth development—often creating big disparities in opportunities and outcomes. Adults also play a pivotal role and can give young people a better chance at successful lives by understanding and intentionally nurturing their development.

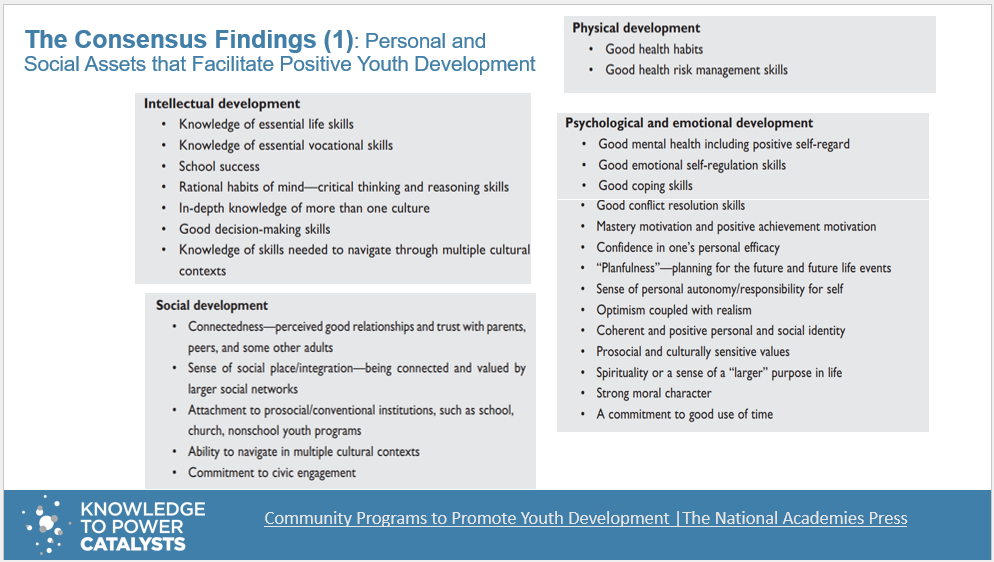

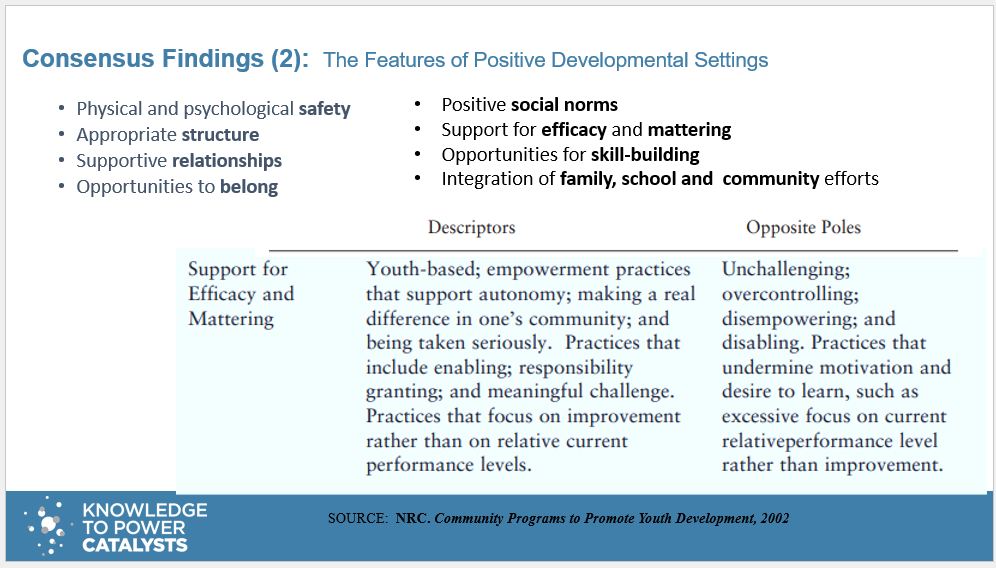

Two charts in the 2002 NRC report galvanized the positive youth development field:

One defining the range of assets (intellectual, social, physical, psychological, emotional) that facilitate Positive Youth Development. The second describing the features of settings that support positive youth development.

Both of these lists stand up well 20+ years later. The categories under which assets are grouped vary, but the list of specific assets has been surprisingly constant. They can be found in CASEL’s SEL Competencies, in the developmental outcomes lists of many youth development organizations, and in the list of the top 100 “durable skills” identified by America Succeeds in their 2022 report that analyzed more than 82 million job descriptions across 22 occupational sectors.

The features of developmental settings are consistent with the SoLD Alliances non-negotiables. The NRC report has added weight because it offers descriptors of what each feature looks like when it is well executed and when it is not.

NRC Takeaways: No one has or needs to be strong on all of these assets, but more is better and more varied is better. Settings that actively work against the developmental features can do harm. Community programs have the commitment, access and flexibility to change trajectories.

Developmental assets are different from and more plentiful than opportunities.

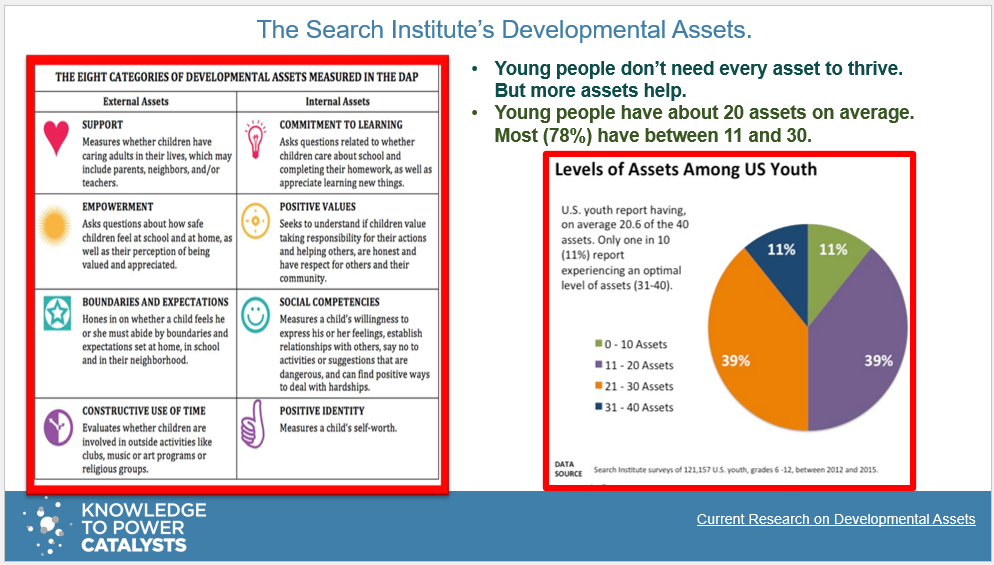

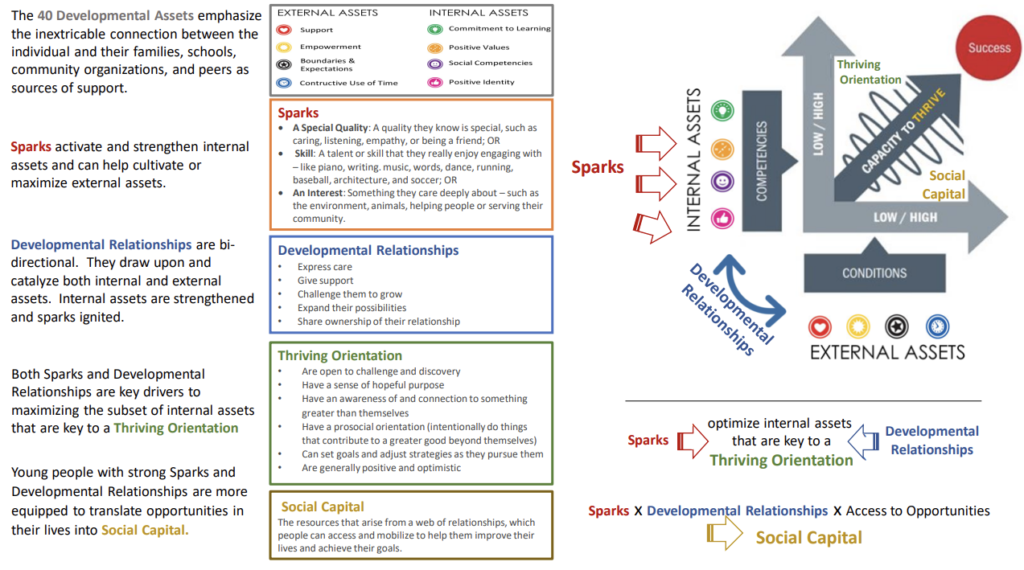

The Search Institute is among a cadre of youth development research organizations who offered simple, actionable, evidence-based frameworks that helped parents, practitioners, and policy makers cut through the piles of recommendations on how to address youth problems and promote youth success. Their conceptual yet practical contributions go well beyond the 40 Developmental Assets, which they have unbundled over the decades. But this foundational work was critical for communicating the idea that every young person, regardless of circumstance, has strengths within themselves and supports in their lives. These may not be sufficient to overcome institutional and systemic inequities, but their proximate importance should not be overlooked.

Search Institute intentionally combined these assets in a single framework to emphasize the dynamic connection between the individual and their families, schools, community organizations, and peers. 20 reflect a young person’s commitment to learning, positive values, social competencies, and positive identity. 20 reflect caring support, empowerment, expectations, and involvement in outside activities. Their findings helped bring currency to the positive youth development approach by demonstrating the value of this approach to all young people, not just “at risk youth.” Key findings include:

Young people don’t need every asset to thrive. Young people have about 20 assets on average. Most (78%) have between 11 and 30.

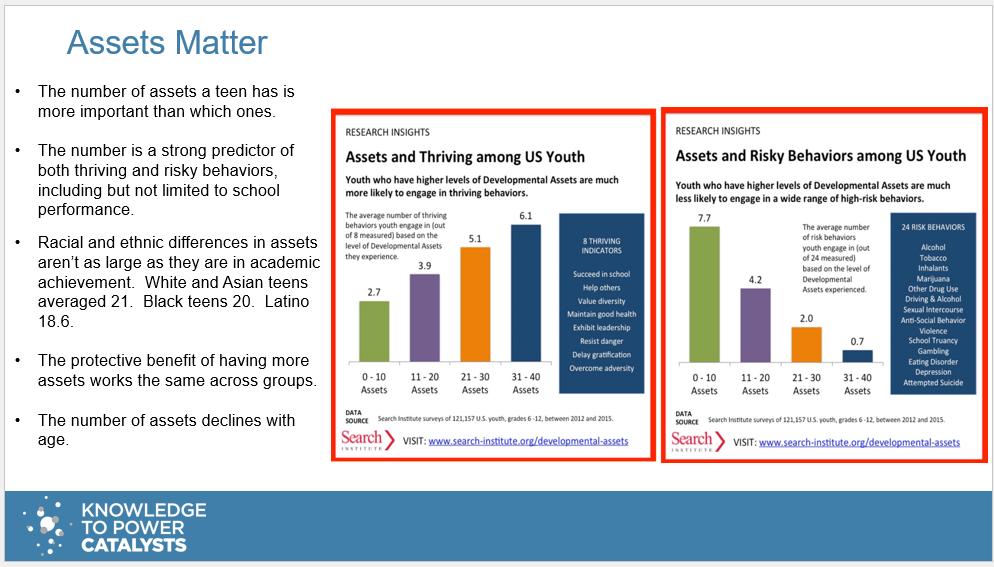

The number of assets a teen has is more important than which ones. The number is a strong predictor of both thriving and risky behaviors, including but not limited to school performance.

Racial and ethnic differences in assets aren’t as large as they are in academic achievement. White and Asian teens averaged 21. Black teens 20. Latino 18.6. The protective benefit of having more assets works the same across groups.

The average number of developmental assets young people have drops 4 points from 6th to 12th grades.

Search Institute Takeaways. Combined, these findings demonstrate the importance of differentiating between the proximate developmental assets that contribute to a thriving orientation and the larger economic and social factors that create thriving opportunities. Building strong developmental relationships with young people (expressing care and providing support, but also challenging growth, expanding possibilities, and sharing power) to help them develop their spark (the thing they are passionate about, committed to, and good at) helps them build social capital, even in environments with relatively sparce opportunities.

Most American’s agree with the developmental researchers. These are minimal benchmarks for youth success. The final question was whether there is longitudinal data to show the impact of these proximate assets or supports on teen’s developmental outcomes at the end of high school and whether the advantages as high school graduates carry into young adulthood.

Productive. Healthy. Connected.

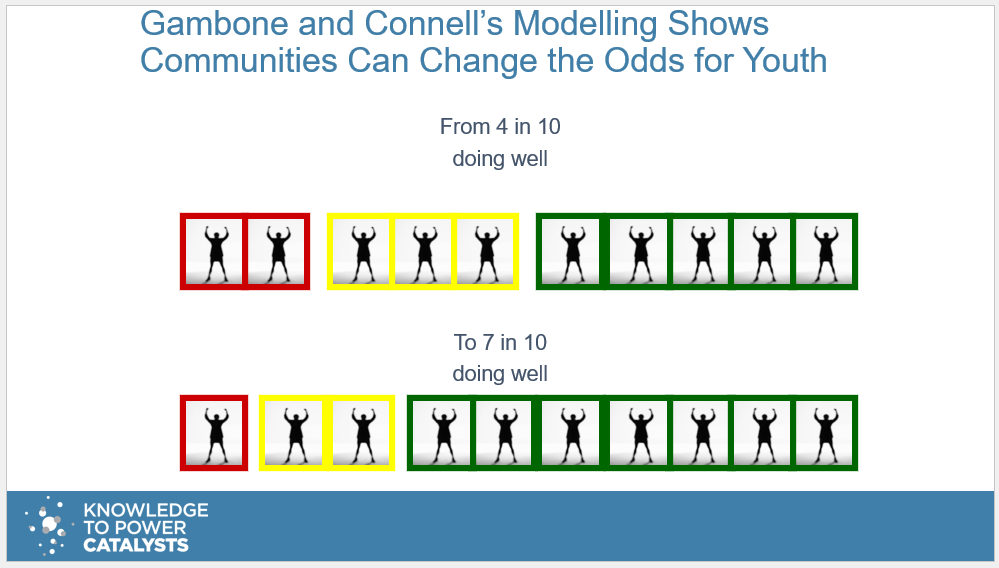

In a 20-year-old landmark study, youth development researcher Michelle Gambone and colleagues at Youth Development Strategies Inc. took up this challenge. Building a longitudinal data set from multiple research studies, they identified easily understandable indicators for young adults in their early twenties (20-24) for each of the three big success areas (e.g., being productive meant being employed or in post-secondary education). They then pulled out the “bookend groups” – those who were doing well in these life areas and those who were really struggling. They then used longitudinal data to tease out what contributed to their success and, equally important, what difference it would make if these ingredients were in place as you followed students from their entry into high school into young adulthood. Their conclusions were cause for both outrage and optimism:

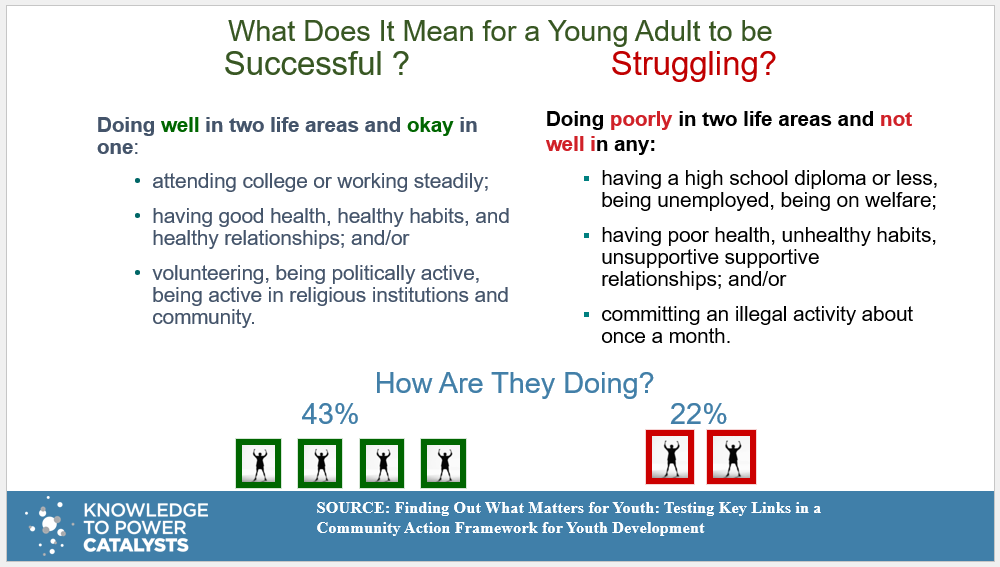

Only 42 % of young adults were doing well in any 2 of the 3 basic areas: Productive (employed or in post-secondary schooling), healthy (managing health risks, engaged in healthy relationships), and connected (voting, participating in religious, community or civic organizations). 22% were doing well in none and were actively in trouble in at least one area (e.g., dropped out, committing criminal acts once a month).

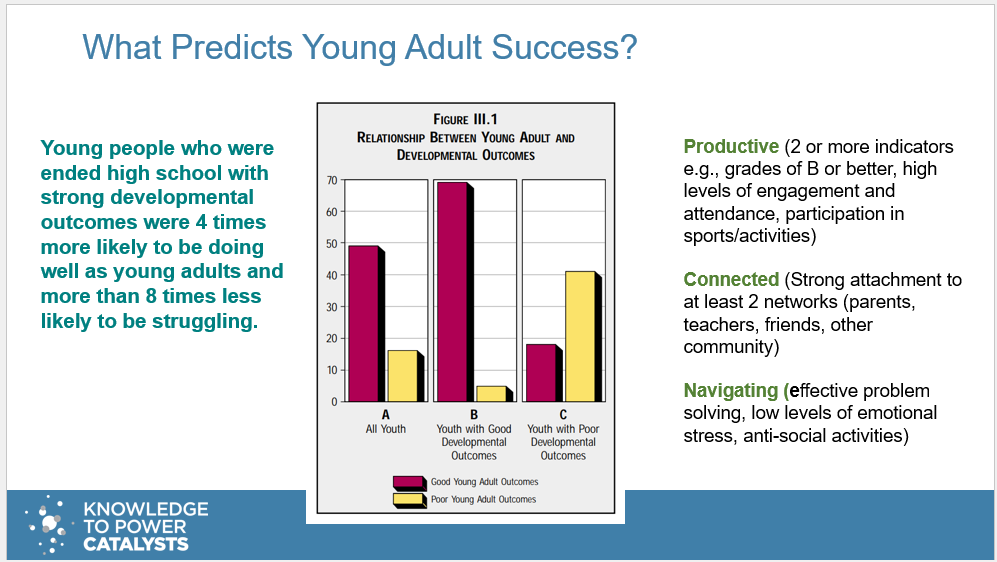

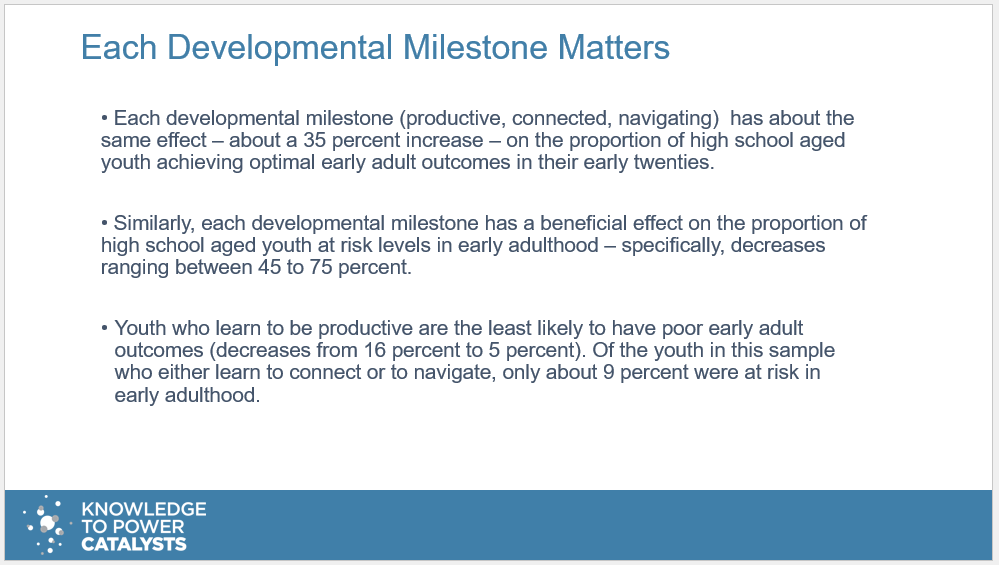

Seniors who were productive (graduating with good grades and plans, having healthy relationships throughout their high school years, developing navigational skills to help them avoid risky behaviors) were 4 times more likely to be doing well as young adults and 8 times less likely to be in trouble.

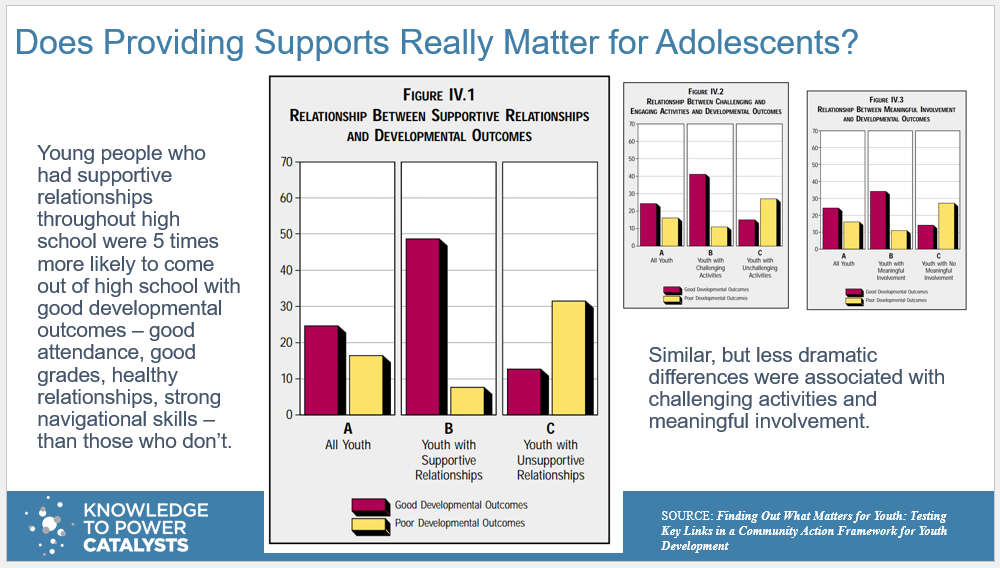

Learners who had strong positive relationships, challenging and engaging learning experiences, and opportunities for meaningful involvement, contribution, and membership throughout their high school years were 5 times more likely to be graduate fully prepared for the next phase of life. Having strong developmental relationships gives young people as much of a boost as having challenging learning experiences or meaningful opportunities to connect and contribute.

- Seniors who were productive (graduating with good grades and plans, having healthy relationships throughout their high school years, developing navigational skills to help them avoid risky behaviors) were 4 times more likely to be doing well as young adults and 8 times less likely to be in trouble.

- Learners who had strong positive relationships, challenging and engaging learning experiences, and opportunities for meaningful involvement, contribution, and membership throughout their high school years were 5 times more likely to be graduate fully prepared for the next phase of life. Having strong developmental relationships gives young people as much of a boost as having challenging learning experiences or meaningful opportunities to connect and contribute.

These percentages could change dramatically, however, if families and community adults had more capacity to support youth, if public institutions including but not limited to schools fully supported youth development, and if communities were filled with high-quality developmental activities. Simulation analysis found if every high school student received these sustained supports from people in any of the places where they spend their time, the percentage of young adults who are doing well could increase from 42 to 68% and the percent in trouble could be reduced from 22 to 12%.

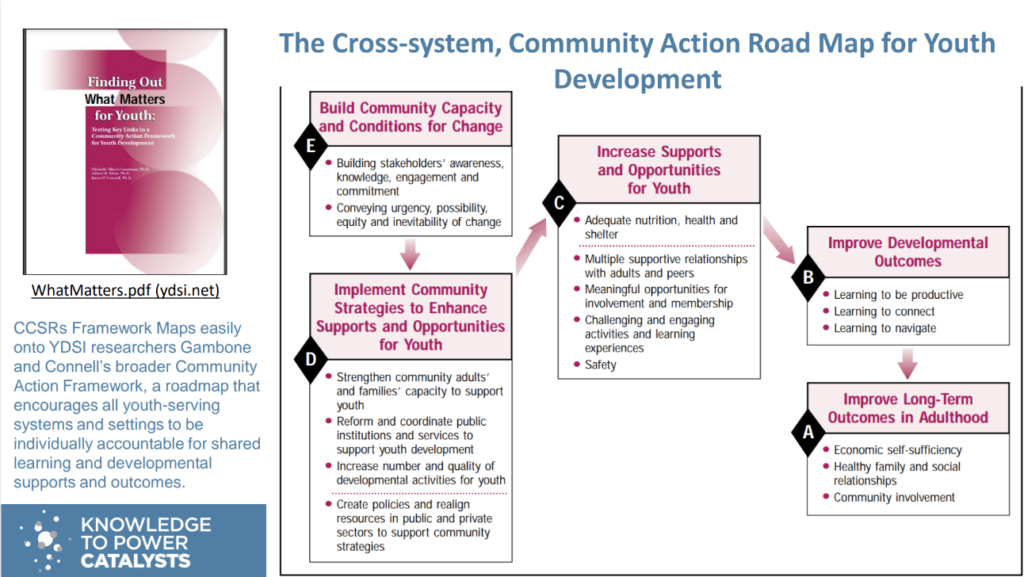

The framework seeks to address five questions:

What are our basic long-term goals for youth? (Box A)

What are the critical developmental milestones or markers that tell us young people are on their way to getting there? (Box B)

What do young people need to achieve these developmental mile-stones? (Box C)

What must change in key community settings to provide enough of these supports and opportunities to all youth that need them? (Box D)

How do we create the conditions and capacity in communities to make these changes possible and probable? (Box E)

YDSI’s Takeaways. Gambone and her colleagues put their takeaways into a Community Action Framework for Youth Development. Having demonstrated the impact of providing developmental supports on high schoolers’ developmental outcomes and the impact, in turn, of their readiness as teens on their success as young adults, the team went beyond the research to put three final steps into the causal equation:

Create policies and realign resources in public and private sectors to support community strategies.(D)

Build stakeholders’ awareness, knowledge, engagement and commitment. (Box E)

Convey the urgency, possibility, equity and inevitability of change. (Box E)

Supporting Young Adult Success

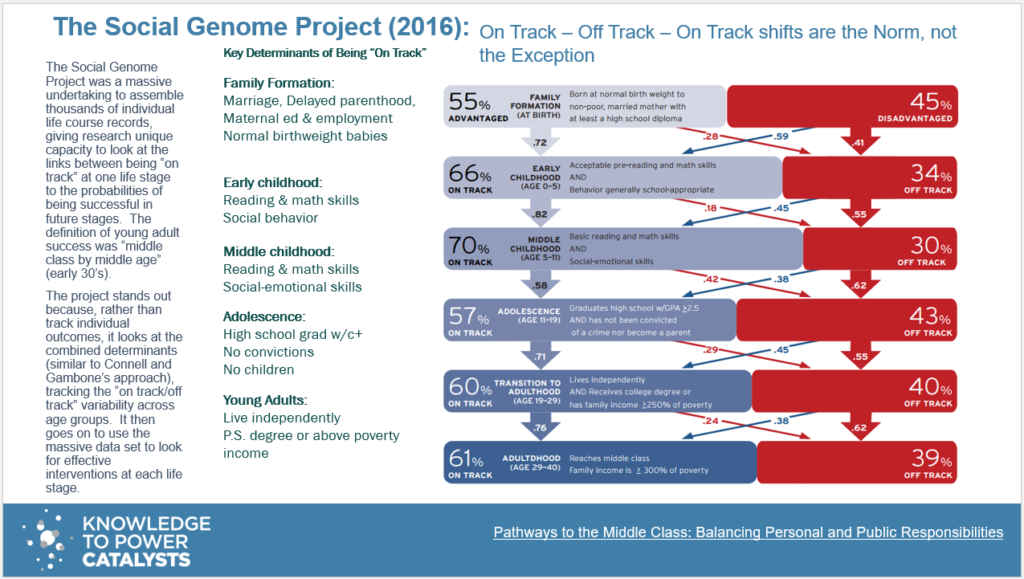

Supporting young adult success requires broader definitions of readiness (beyond academic success). It also requires a greater appreciation of the resilience children and adolescents have precisely because their destinies are not predetermined by their genes. The work of the Social Genome Project demonstrates this idea at a very high level by challenging our assumptions that young people who are “off track”, especially in their early teen years, are doomed to failure

The Social Genome Project was a massive undertaking to assemble thousands of individual life course records, giving research unique capacity to look at the links between being “on track” at one life stage to the probabilities of being successful in future stages. The definition of young adult success was “middle class by middle age” (early 30’s).

The project stands out because, rather than track individual outcomes, it looks at the combined determinants (similar to Connell and Gambone’s approach), tracking the “on track/off track” variability across age groups. It then goes on to use the massive data set to look for effective interventions at each life stage.

The Project demonstrated that:

The chances of making it into the middle class by age 30 (defined as at least 300% above the poverty line) were greatest for those on track the whole time (81%), but those off track only one or two periods before young adulthood (74-80%) also did well.

60 % of young people who were off track from early childhood through adolescence (3 periods) achieve middle class success.

Young people who were off track in all periods had the lowest rates (24%). But being off track in adolescence and young adulthood mattered the most. Only 36% achieved adult success who had been on track until adolescence and didn’t turn it around in young adulthood.

The Social Genome Project was a massive undertaking to assemble thousands of individual life course records, giving research unique capacity to look at the links between being “on track” at one life stage to the probabilities of being successful in future stages. The definition of young adult success was “middle class by middle age” (early 30’s).

The project stands out because, rather than track individual outcomes, it looks at the combined determinants (similar to Connell and Gambone’s approach), tracking the “on track/off track” variability across age groups. It then goes on to use the massive data set to look for effective interventions at each life stage. The Project demonstrated that (read slide)

Most public sector interventions are focused on fixing problems – on helping children and families that have gotten off track get on track. The Project’s analyses found that big public investments – like Head Start – made a difference in every dev. period except for adolescence.

This takes us back to the findings that started the PYD movement – just focusing on fixing or even preventing teen problems doesn’t work. We have to respect adolescents’ built in drive to be productive, be connected, have the skills and confidence needed to be healthy and make good choices. We have to acknowledge their challenges and be prepared to help them address them, while also helping them leverage their assets.

PYD approaches respect the fluidity of development, the interplay between competencies and contexts/conditions. By focusing on building young people’s capacity to thrive they equip them to take advantage of opportunities and bounce back from adversity.

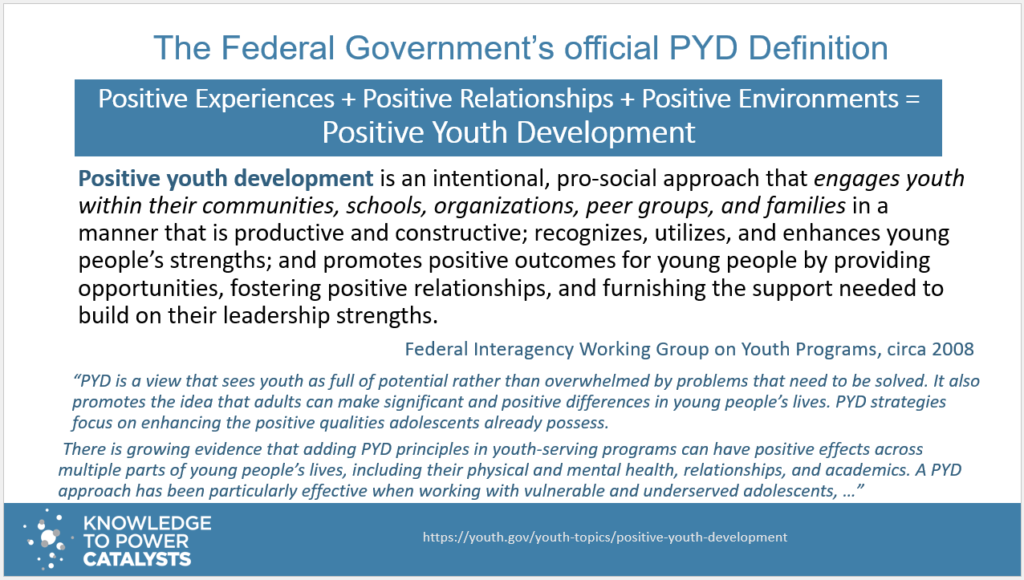

The Federal Government’s Definition of PYD

More than a decade ago, 23 federal agencies (including the Department of Education) agreed to embrace the Positive Youth Development approach as the most effective way to support “at risk youth.”

The definition and the mantra – positive experiences + positive relationships + positive environments = positive youth development – are applicable to all young people. And youth and community organizations already using this approach eagerly championed the Federal government’s official acknowledgement.

But, as noted earlier, because of the focus on prevention and remediation, the Federal Interagency Working Group on Youth Programs – and the broader PYD movement – did not prioritize bringing this approach into the classroom.

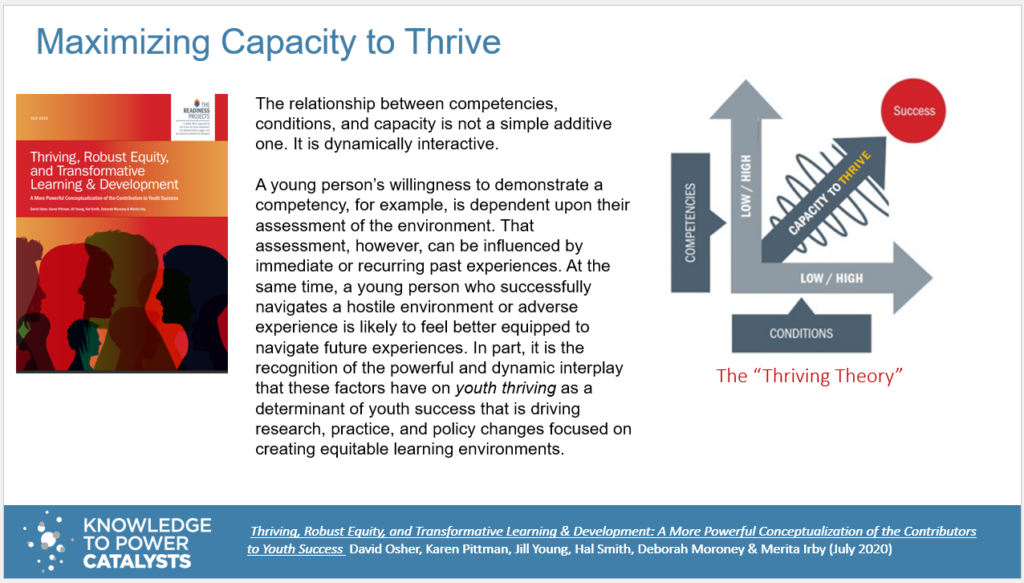

The relationship between competencies, conditions, and capacity is not a simple additive one. It is dynamically interactive. A young person’s willingness to demonstrate a competency, is dependent upon their assessment of the environment. That assessment can influenced by immediate or recurring past experiences. At the same time, a young person who successfully navigates a hostile environment or adverse experience is likely to feel better equipped to navigate future experiences. In part, it is the recognition of the powerful and dynamic interplay that these factors have on youth thriving capacity as a determinant of youth success that is driving R, P, &P changes focused on creating equitable learning envs.

Success: Success is a relative term. But for most people, a successful young person is productive (in school, employed, on a path towards economic self-sufficiency), healthy (managing physical and emotional health, avoiding high risk behaviors), and connected (involved in/contributing to something bigger than themselves).

Competencies. Basic academic competence (fundamental literacies, foundational knowledge) is necessary but not sufficient. There is a range of competencies or assets that young people can build to support their development (e.g., Intellectual, Social, Emotional, Physical, Civic). More is better, but no one needs to excel in all areas. Having a strong identity, or sense of self, and a strong sense of agency are also major assets.

Conditions. Broad social and economic conditions, including racism and poverty, clearly affect young people’s chances of success. But there is a range of contexts or settings (people in places) in which development can be supported (e.g., families, schools, neighborhoods, community organizations, peer groups, work environments) that can ameliorate these broad inequities. Settings that support development share a common list of characteristics. Settings that not only do not provide these characteristics but operate in opposition to them can do harm.

Search Institute’s work on Thriving, Sparks and Developmental Relationships is critical to our understanding of what we can do to help young people fully leverage their internal and external assets, especially when faced with broader or more systemic limiting conditions. I’m sure many of you are familiar with Search’s research and frameworks in these areas. What I’d like to do as I wrap up this presentation is show you a visual we (KP Catalysts) have been working on with Search to show how these important concepts connect.

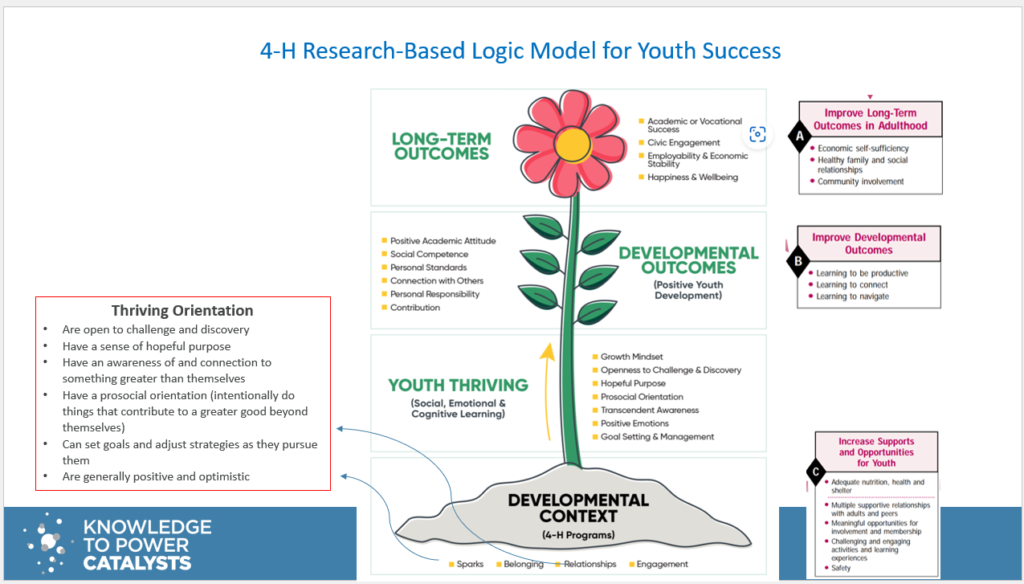

All of these research (and more) has been incorporated into the 4-H research based model for Youth Success. The model is particularly useful for practitioners because it:

I’ve talked long enough now. Let me pause to invite Mary onto the screen to share reflections and field questions.

Separates out the assets associated with a thriving orientation from the broader developmental outcomes. These more proximate assets are directly influenced by the quality of the developmental relationships in a teens’ lives as well as by the motivational boost they get from having their sparks supported.

Does not hesitate to link the developmental outcomes to long-term outcomes society values.

I’ve talked long enough now. Let me pause to invite Mary onto the screen to share reflections and field questions.